Canada’s First Anti-Drone Prison Task Force Cuts Contraband Drops 50% In Nine Months

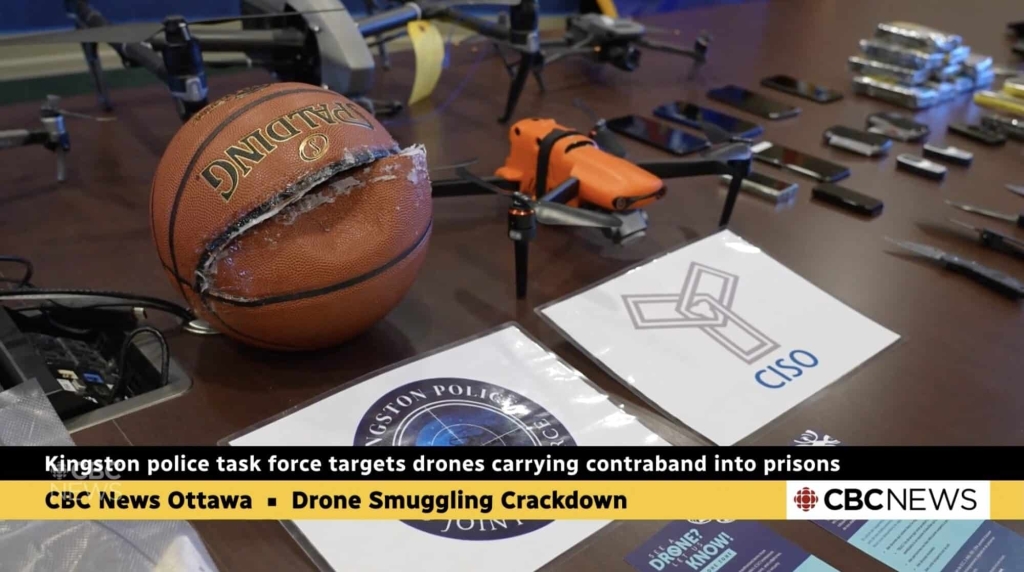

A basketball stuffed with tobacco and cellphones. Ceramic knives that slip past metal detectors. Drones equipped with deep-sea fishing release mechanisms. These are just some of the seized contraband items displayed by a groundbreaking joint task force in Kingston, Ontario—Canada’s first dedicated anti-drone smuggling operation targeting correctional facilities.

After nine months of coordinated operations, the pilot project has successfully cut drone drops by approximately 50% at Kingston’s four federal prisons, according to Kingston Police and Correctional Service Canada officials, reports CBC. The initiative represents a proof-of-concept that could reshape how facilities worldwide combat the rapidly escalating aerial contraband crisis.

First-of-Its-Kind Collaborative Enforcement Model

The Kingston task force brings together the Kingston Police Intelligence Unit, Correctional Service Canada (CSC), and Canada Border Services Agency in an unprecedented partnership specifically targeting drone smuggling operations. Unlike traditional approaches that rely primarily on detection systems, this integrated model coordinates enforcement both inside and outside prison walls.

“Kingston is a prison town,” said Sgt. Jonas Bonham, head of the Kingston Police Intelligence Unit. “It just made sense for us to join forces and start doing it together.”

The task force has pursued suspects across the country and shared operational knowledge with other police forces and correctional facilities, positioning Kingston as a potential blueprint for addressing what has become a national security crisis. Canada reported 1,064 drone incidents at correctional facilities in 2024 alone, up from 899 in 2023-2024—a trend that began accelerating around 2016.

Sophisticated Smuggling Operations Worth Hundreds of Thousands

The contraband economy inside Kingston’s prisons operates on a massive scale. A recent seizure following suspected drone drops yielded tobacco, marijuana shatter, and cellphones with an estimated institutional value of $338,745, according to CSC.

Inside prison walls, contraband prices inflate to 10-25 times street value, creating enormous profit incentives for smuggling networks. Drones costing $6,000-$10,000 are considered acceptable business expenses when a single successful delivery can generate tens of thousands in institutional-value goods.

“These things are ordered,” Bonham explained, describing how cellphones inside prisons coordinate each delivery. “They hope it gets delivered. We hope we intercept it.”

Joel Blacklock, a CSC senior project manager whose portfolio includes counter-drone technologies, emphasized the program’s impact:

“This task force, with its dedication to this specific issue, is making a huge difference.”

From Lawn Chairs to Fishing Gear: Evolving Tactics

When Kingston Police first started intercepting drone operations around 2020, smugglers had grown so comfortable they set up lawn chairs on rooftops near Collins Bay Institution, one of the city’s four federal prisons. The facility’s distinctive red roof, turrets, and towers made it an easy target from a nearby grocery store parking lot—what Bonham described as “the original launch location” for much of Kingston’s smuggling activity.

“We arrested them mid-launch,” Bonham recalled of his first interception. “Then we had to figure out how to land the drone with the package attached to it.”

Since then, smuggling techniques have grown increasingly sophisticated. Operators use deep-sea fishing release mechanisms originally designed to drop bait far from shore, now repurposed to precisely deploy contraband packages. Smugglers camouflage packages with fake grass, wrap them in white fabric for winter drops, and even disguise contraband as sports equipment like basketballs that blend into prison yards.

Drones can be piloted from kilometers away, sometimes from moving vehicles. Before CSC implemented infrastructure changes, some deliveries were made directly to cell windows.

Weapons and Airspace Wars: The Escalating Threat

The task force has observed a troubling trend: more weapons appearing in drone deliveries. These include ceramic blades specifically chosen to evade metal detectors alongside traditional steel knives.

“It’s not like sharpening a toothbrush,” Bonham said. “This is a pretty serious weapon and you could easily kill someone.”

Perhaps most concerning is the emergence of territorial battles over prison airspace itself.

“Rival gangs [are] trying to control who can fly into prisons,” Bonham noted. “The money that they’re making inside the prisons and pumping it back out into the street causes a lot of danger.”

Lee Chapelle, who spent nearly 21 years in various Canadian prisons and now runs Canadian Prison Consulting Incorporated, described the transformation from his experience in the 1980s. Back then, smugglers relied on throwing packages over fences or hiding contraband on or inside their bodies.

“It does sound synonymous with Uber or something along those lines,” Chapelle said of modern made-to-order drone deliveries. The technology gives criminals the ability to smuggle “anything from guns, phones, any illicit drug possible,” he added. “It’s like a bomb, almost, ready to go off.”

Upgraded Charges Reflect Serious Consequences

Recognition of the threat’s severity has evolved Kingston Police’s charging approach. Officers initially charged drone smugglers with simple mischief. Those charges have been upgraded over the years to mischief endangering life—an acknowledgment that drugs and weapons smuggled into prisons create life-threatening conditions.

“We are suggesting that when you introduce contraband into an institution, it becomes currency,” Bonham explained. “That’s when violence comes in. It makes it very dangerous for staff, very dangerous for inmates.”

The sudden influx of drugs, weapons, and phones ratchets up the risk of inmates falling into debt and suffering violence inside facilities.

Chapelle described the resulting environment as feeling “similar to a war zone,” adding there is “a legitimate need for corrections and for the police to step up their game to contend with the technological advances.”

DroneXL’s Take

Kingston’s success story arrives at a critical moment for correctional facilities worldwide. As we’ve extensively documented, prison drone smuggling has exploded into a full-scale crisis affecting institutions from Georgia’s Operation Skyhawk RICO case involving a drone shop owner to repeated busts across South Carolina facilities to Canada’s own escalating problem.

What makes Kingston’s approach revolutionary is the collaborative enforcement model. Most facilities remain limited to detection-only systems due to legal restrictions on counter-drone mitigation technology. By integrating police, corrections, and border agencies, Kingston has created a framework that doesn’t just detect threats—it systematically dismantles smuggling networks through coordinated arrests both inside and outside prison walls.

The numbers tell the story: Canada went from 899 drone incidents in 2023-2024 to 1,064 in 2024 alone. The UK reported 1,296 incidents in just ten months ending October 2024—a tenfold increase since 2020. Georgia documented over 1,000 “drone incidents” since 2022. Washington State Prison in Georgia alone saw deputies intercept 21 attempted drops in 2024, resulting in 43-45 arrests.

This isn’t a technology problem requiring expensive counter-UAS systems alone—it’s an enforcement problem that demands coordinated human intelligence, surveillance, and prosecution. Kingston has proven that dedicated task forces can cut the problem in half while building cases that lead to serious charges rather than simple misdemeanor citations.

The broader implications extend beyond corrections. Every prison drone incident generates negative headlines that fuel public fear and regulatory overreach affecting legitimate drone operators. When a giant 5-foot-wide drone was used to smuggle contraband into a Louisiana federal prison or when South Carolina busts revealed sophisticated commercial-grade equipment, these stories reinforce the false narrative that drones are primarily tools for criminals rather than the transformative technology we know them to be.

Kingston’s replicable model offers a path forward that protects facilities without imposing blanket restrictions on responsible operators. Blacklock’s hope that other jurisdictions will follow Kingston’s example isn’t just optimistic—it’s essential.

“We’re hoping that other law enforcement might be interested in following Kingston city police … and how they’re tackling our drone issues,” he said.

The question now is whether other prison systems will learn from Kingston’s success before the crisis escalates further. The technology exists. The tactics work. All that’s missing is the institutional will to replicate what Canada has proven possible.

What do you think about Kingston’s collaborative enforcement approach? Should other jurisdictions adopt similar dedicated task forces? Share your thoughts in the comments below.